Nov 12, 2025

Thomson Safaris Named Tripadvisor Travelers’ Choice Awards Winner for 2025

We’re thrilled to announce that Thomson Safaris has been named a winner in Tripadvisor’s Travelers’ Choice Awards for 2025! This prestigious honor comes from the people who matter most: our…

Jul 08, 2025

Voted a “World’s Best” African Safari Outfitter by Travel + Leisure in 2025

We’re thrilled to announce that Thomson Safaris has once again been named one of the World’s Best African Safari Outfitters by Travel + Leisure readers in its prestigious 2025 World’s Best Awards…

Jul 01, 2025

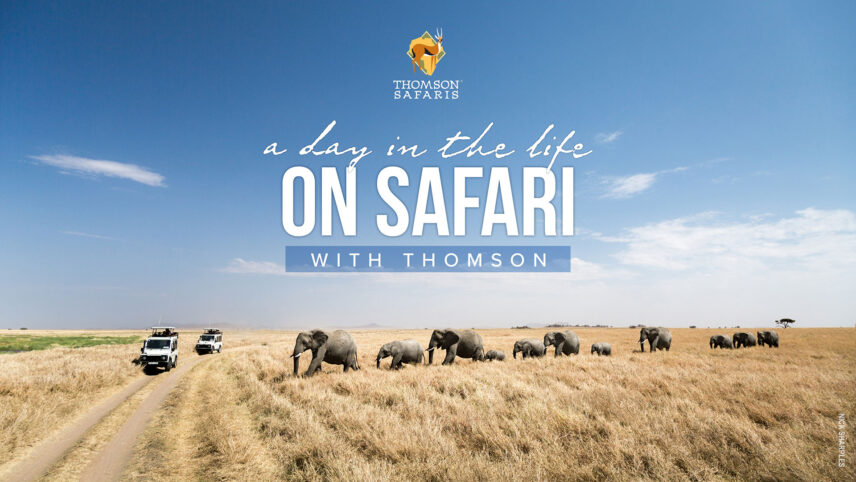

A Day in the Life on Safari [Webinar]

Ever wondered what it’s really like to be on safari in Tanzania? From the thrill of early morning wildlife drives to the quiet magic of evenings around the campfire,…

Jun 23, 2025

Top Adventure Tour Operator: 3 Years on USA Today’s 10Best List

We’re honored to share that Thomson has been named one of USA Today’s 10Best Adventure Tour Operators for the third year in a row! That’s 2023,…

Mar 26, 2025

Advice from Tanzanian Staff: Insider Tips for a Perfect Trip

Guests can attest that Thomson brings the magic of Tanzania to life! The dedicated team in Boston, MA handles the logistics and planning while the expert crew on…

Nov 25, 2024

Meet Safari Camp Chef Rebeka Maronde

Ever wonder who is behind those delectable meals on safari? Meet Chef Rebeka Maronde, a rising star in the Tanzania culinary scene. She is one of the many top chefs…

Jul 21, 2024

Over 40 Years of Sustainable Travel

From the beginning, our founders Rick Thomson and Judi Wineland believed that tourism should be a force for good. Eco-friendly practices and a commitment to bringing high-paying, stable jobs…

Jul 18, 2024

7 Reasons to Go on a Family Safari with Thomson

Safaris can be life-changing trips, but there are few experiences for kids that are more powerful. Imagine seeing the majesty of the Big 5 as a little one: that’s an…

Jul 10, 2024

Travel + Leisure voted us a World’s Best Safari Outfitter for 2024!

We’re overjoyed to announce that Travel + Leisure readers have chosen us as one of the World’s Best Safari Outfitters for the eighth time! We’d like to thank every person who voted…

Jul 01, 2024

Thomson Co-Founders Reminisce on the Dawn of Adventure Travel

In celebration of Thomson’s fortieth anniversary, we sat down with Thomson co-founders Rick and Judi to hear stories from the early days of their careers, and how those formative…

Jun 07, 2024

What was a Thomson Safari like 40 years ago?

Campfire meals, tiny A-frame tents and gargantuan trucks: these were the facts of life for visitors to Tanzania in the 1980s, when safari travel was in its infancy. Even though…

Apr 30, 2024

VIDEO: Go Behind the Scenes of a Nyumba Tent with Rick Thomson

After 40 years in the Tanzania bush, Rick Thomson, one of the co-founders of Thomson Safaris, developed the perfect safari camping experience: the Nyumba. These tents were designed…