After the lions have feasted and the leopards have lunched, vultures swoop in to grab a bite of the remains. These master scavengers are the most common raptors you’ll spot on a Tanzania safari. But you don’t need binoculars to see they don’t get a lot of love.

Their unattractive hunch and diet of decaying carrion have earned themselves quite a terrible reputation: harbingers of death, forever associated with the stench of rot. Do they deserve it?

To answer that, let’s see what vultures bring to the table.

What Do Vultures Do?

Vultures’ hankering for carrion is a critical part of the Serengeti’s ecological stability. In fact, we might not have a Serengeti without them.

- Vultures recycle nutrients. Vultures break carcasses down to their bones, quickly recycling nutrients back into the environment.

- Vultures prevent the spread of disease. Vultures have acidic stomachs that can digest highly toxic substances found in decaying flesh, such as anthrax, tuberculosis and even rabies. Without scavengers, these diseases would pollute waterways and pose a major threat to the environment.

- Vultures control fly populations. By reducing the amount of food available for flies, that population is kept in check, further reducing the spread of disease.

How do Vultures Find Food?

Carcasses are common in Tanzania, but they’re not plentiful, and good scavengers must cover great distances to find them. Contrary to popular belief, vultures don’t sniff for their meals, as they don’t have a strong sense of smell.

Lion protects its kill from approaching vultures

Instead, vultures employ their sharp eyesight to fly high and scan the ground for their meals, flying up to 124 miles a day in search of food. It’s believed they can spot a three-foot carcass from four miles away in the Serengeti’s open plains.

The Pecking Order

When scavengers make a kill, they dig in quickly–they can clean a body in less than half an hour.

Lappet-faced vulture and jackal in a face-off; the wingspan of a Lappet-faced vulture can measure up to 9.5′

But there’s a pecking order to the kill. It’s not a rigid hierarchy, but generally, there’s a system to who eats when:

First, predators and hyenas. Next, jackals and Marabou storks. Lastly, vultures.

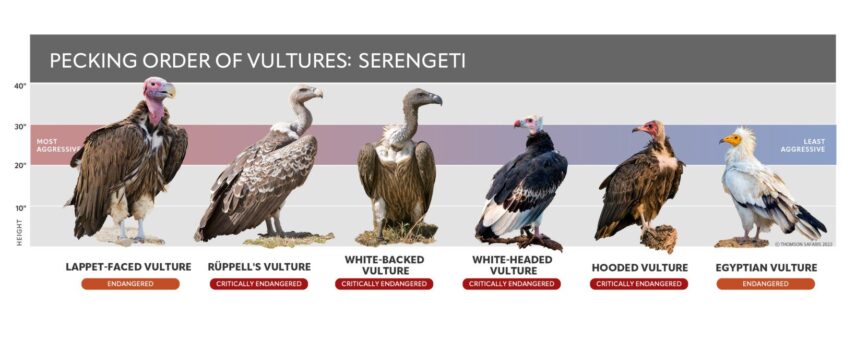

Vultures tend to bicker over the best spot at the dinner table, squawking and pecking and shoving each other around. But there’s even a pecking order among vultures, determined by their size and level of aggression.

The Pecking Order Among Vultures

- 1: Large, aggressive lappet-faced vultures dominate the kill and eat first, using their powerful beak to open the skin of the carcass. Their heads are a bald, bullish red, which keeps their feathers clean and helps the sun bake any bacteria stuck to the surface.

- 2: Rüppell’s vultures come after, and have been known to climb inside the ribcage of a carcass to feed. Their power to find carrion lies in their ability to search from record-breaking heights. Rüppell’s are the highest-flying birds in the world; aircraft have documented a collision with a Rüppell’s at over 36,000 feet.

- 3: White-backed vultures are next. Their beaks aren’t strong enough to open tough skin like the Lappet-faced vulture, so they only chomp on soft tissue. They’re known to gorge themselves to the point where they can’t fly.

- 4: White-headed vultures wait on the periphery before devouring ligaments and bones. Unlike most vultures, White-headed vultures are solitary and usually don’t commingle with more than a single partner.

- 5: Hooded vultures move in once the larger vultures have flown off. They use their pointed bills like tweezers to select hard-to-reach ligaments and connective scraps that the larger vultures couldn’t access.

- 6: Egyptian vultures are the smallest of Tanzania’s raptors and last in the pecking order. But these clever birds don’t only eat carrion! Their diet also consists of the eggs of larger birds, such as ostriches, flamingos and pelicans. Egyptian vultures will drop stones onto the eggs to crack them open, making them one of the few bird species known to use tools!

Vultures are careful eaters–imagine a prim dinner guest with a napkin bib. Most don’t like blood on their feathers. They yank small scraps from the kill and clean every hunk of meat from the bone. When they’re done, the carcass is spotless–if there’s anything left at all.

Occasionally, hyenas will wait for lappet-faced vultures to pierce the carcass so they can access the meat inside. Thomson guest Ken Rivard witnessed this firsthand on his Taste of the Wild safari:

“We got an up close and very personal view of what happens to buffalo attacked by hyenas,” Ken said. “The buffalo will be taken down by the hyenas, then the hyenas will back off and let vultures descend and open the animal up. Then, the hyenas go back in and chase the vultures off. They feed. Nothing gets left over.”

Do Vultures Hunt?

All scavengers scavenge differently, and some vultures occasionally hunt, too. They prey on insects, lizards, smaller birds and rodents. The ambitious white-headed vulture doesn’t mind hunting for mammals such as porcupines, bat-eared foxes, genets, hyraxes, hares and even monkeys.

The Threat to Vultures

In Tanzania and countries across Africa, vulture populations have declined in recent years. This is due to the increasing prevalence of poisoning, hunting and human development.

Farmers have been known to poison dying animals and let vultures feed on them, killing as many as 100 birds at once. These raptors are also hunted for their body parts and sold for use in traditional medicine, despite having no medicinal value. And because vultures look with their peripheral vision when they fly (not straight ahead), they’re susceptible to collisions with power lines, cell towers and windmills.

Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA) has been monitoring vulture populations with surveys and satellite tagging since 2013. This initiative provides data on vulture populations that can help conservationists protect them.Farmers have been known to poison dying animals and let vultures feed on them, killing as many as 100 birds at once. These raptors are also hunted for their body parts and sold for use in traditional medicine, despite having no medicinal value. And because vultures look with their peripheral vision when they fly (not straight ahead), they’re susceptible to collisions with power lines, cell towers and windmills.

Still, it’s a tough world for vultures. Scant pickings, fierce competition and a bad reputation are part and parcel of their existence. But we ought not to have a bone to pick with them–they fulfill a critical ecological niche that keeps the rest of the environment cleaner, healthier and free of toxic diseases for wildlife and people.